Abstract

Pre-gelatinised flaked cereals are frequently used as purposeful formulation tools rather than simple extract extenders, yet their effects are often presented ingredient-by-ingredient rather than through shared mechanisms. This short communication synthesises brewing literature to provide a compact framework linking flaked adjunct composition and structure to wort chemistry, processability, and sensory outcomes under conventional mash conditions. Emphasis is placed on (i) starch accessibility, notably the practical consequence of pre-gelatinisation in flakes, which shifts the constraint from starch swelling to malt enzyme reserve and stability, and (ii) soluble non-starch polysaccharides (especially β-glucans and arabinoxylans) that modulate wort viscosity, separation performance, haze tendency, and perceived fullness. A table intended as a rapid decision aid is presented as a conclusion of this short communication.

1. Introduction

Brewing formulation is increasingly approached as ingredient engineering: grist composition is used to tune fermentability, wort rheology, colloidal stability, and sensory texture, not merely original gravity. In this context, flaked cereal adjuncts (typically steamed/rolled and pre-gelatinised) offer a high-accessibility route to modify wort composition because they deliver readily mash-convertible substrate alongside variable loads of proteins, lipids, and viscosity-active cell-wall polymers. Their impact therefore propagates from mashing and wort separation into measurable outcomes such as extract efficiency, attenuation, viscosity, and filtration behaviour, ultimately shaping palate fullness, foam, and clarity. A mechanistic synthesis is useful as a compact decision framework, translating brewing science into formulation choices.

A central constraint is the coupling between substrate accessibility and malt enzyme capacity. Whereas raw cereal grits or whole grains can require staged heating to achieve starch gelatinisation within an enzyme-active environment, flaked adjuncts are generally pre-gelatinised, and conversion is more often limited by available amylolytic activity, mash regime (temperature, time, acidity), and the competitive effects of other macromolecules on mass transfer and separation. This distinction matters practically: with flakes, the decision focus is: can the mash convert it predictably without compromising processability?

A second, frequently limiting axis is wort rheology driven by soluble cell-wall polysaccharides. β-Glucans can elevate viscosity when insufficiently degraded, with downstream impacts on bed permeability, run-off, and filtration robustness. Arabinoxylans, particularly associated with rye and some wheat fractions, can likewise increase viscosity and are often linked to enhanced sensory fullness, illustrating that the same macromolecules that complicate separation can be leveraged intentionally for mouthfeel.

2 Mechanistic families relevant to flaked cereal adjuncts

2.1 Carbohydrates

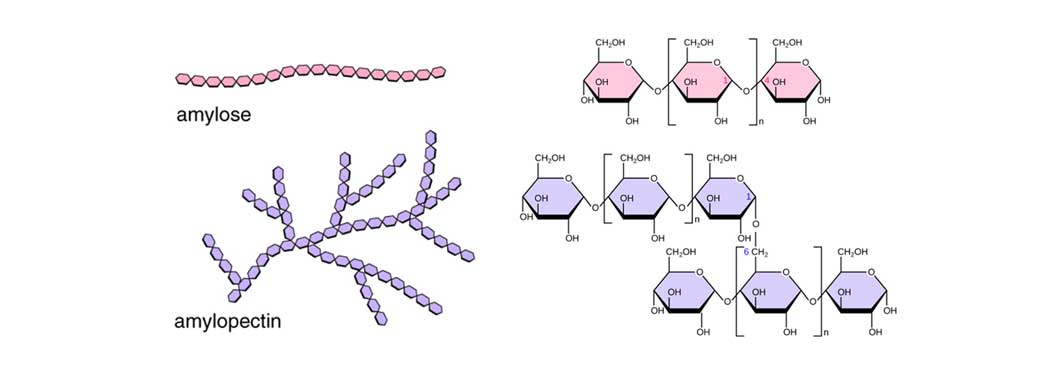

Cereal carbohydrates in brewing are dominated by starch, a composite of amylose (linear polymer of predominantly linear α-1,4 glucan) and amylopectin (highly branched α-1,4/α-1,6 glucan). In the mash, starch must first become physically accessible through hydration and gelatinisation, during which granules lose crystallinity and swell, allowing rapid enzymatic attack. The mash then partitions carbohydrate into a spectrum of soluble products: simple sugars (minor), maltose and maltotriose (typically dominant fermentables), and a distribution of dextrins that remain unfermented under conventional brewery fermentations. This sugar spectrum, rather than extract alone, largely determines apparent attenuation, final gravity, and the balance between dryness and residual sweetness.

From a process standpoint, carbohydrate conversion is constrained by the coupling of starch accessibility to enzyme capacity: adjuncts and flakes generally contribute little or no endogenous diastatic power and rely on base-malt amylolytic activity. Consequently, the same adjunct inclusion rate can yield different outcomes depending on mash temperature–time profile, pH, and the enzyme reserve available in the grist. In practical formulation, “more flaked material” does not automatically imply “more body”; the perceived outcome depends on whether conversion proceeds to fermentables, stalls at dextrins, or is modulated by other macromolecular families that shape viscosity and colloidal structure.

Practical considerations

Treat flakes primarily as substrate (pre-gelatinised starch plus associated macromolecules), not as an enzyme source: ensure sufficient base malt and an appropriate mash regime for complete conversion. Decide on your target fermentability first (final gravity/attenuation) and then use mash parameters and yeast choice to realise it; adjunct choice is a secondary lever.

Figure 1: starch molecular structure

2.2 Non-starch polysaccharides

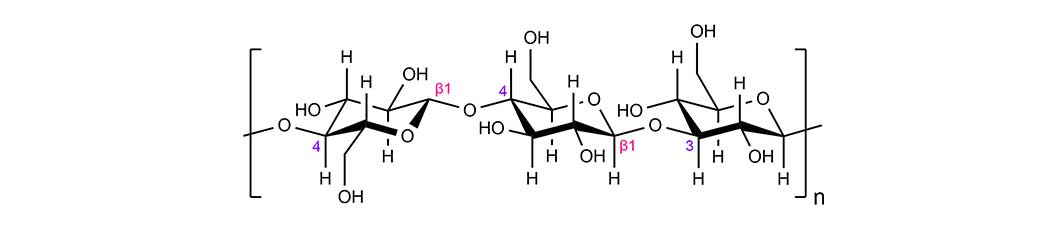

Non-starch polysaccharides (NSPs) are cereal cell-wall polymers that are not fermented by brewing yeast but can be partially solubilised and modified during mashing. Two families dominate brewing relevance: β-glucans (mixed-linkage β-1,3/β-1,4 glucans prevalent in barley and often elevated in oats) and arabinoxylans (xylan backbone with arabinose side chains, prominent in wheat and rye). Their brewing significance is governed less by their absolute mass fraction than by their solubility and molecular weight distribution, which determine how strongly they influence wort rheology.

Mechanistically, soluble high-molecular-weight NSPs increase wort viscosity and can impede mash and lauter performance by reducing permeability and slowing runoff. At the same time, these polymers can enhance perceived palate fullness and “silkiness” by increasing beer viscosity and contributing to colloidal structure. NSPs also participate indirectly in haze formation by promoting mixed macromolecular assemblies with proteins and polyphenols. Thus, NSPs represent a classic trade-off: the same chemistry that supports texture can reduce process robustness and clarity.

Practical considerations

Use NSP-rich adjuncts intentionally: they are effective texture tools, but they raise the probability of slow runoff and filtration difficulties. Plan mitigation (grist handling, mash schedule, and separation aids such as rice hulls) at formulation time rather than treating lauter issues as “bad luck”. If bright beer is the goal, keep NSP-heavy additions moderate or pair them with process controls that limit excessive solubilisation or persistence of high-MW fractions.

Figure 2: molecular structure of β-glucans from cereals showing β-1,4 and β-1,3 bonds

2.3 Proteins and peptides

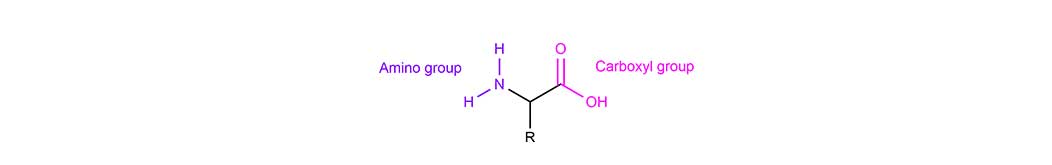

Cereal proteins enter wort as a distribution of intact proteins, polypeptides, and small peptides generated by malting and mash proteolysis. Their brewing functionality is strongly size-dependent: certain higher-molecular-weight fractions are foam-positive and can stabilise bubbles at the gas–liquid interface, whereas intermediate fractions are often implicated in haze formation when they form insoluble complexes with polyphenols (chill haze and, with time, permanent haze). Low-molecular-weight peptides contribute both to mouthfeel and to yeast nutrition, but their sensory role is typically indirect and context dependent.

In the mash and kettle, protein chemistry is shaped by denaturation, aggregation, and removal into hot/cold break. The balance between “useful” soluble fractions and haze-active species therefore depends on raw material selection (malted vs unmalted cereals; husk content; degree of modification), process conditions (pH, temperature, time), and downstream clarification strategy. Importantly, “high protein” is not a single outcome: it can improve foam and perceived structure while simultaneously increasing haze potential and, in extreme cases, affecting separation performance through colloidal loading.

Practical considerations

Target protein functionality rather than protein quantity. If foam and texture are priorities, favour ingredients and regimes that preserve foam-positive fractions while controlling haze-active complexes (via process and clarification choices). Align protein strategy with beer intent: the optimal protein profile differs markedly between a bright lager and a deliberately hazy style.

Figure 3: structure of an amino acid, smallest chain of a protein

2.4 FAN (free amino nitrogen)

FAN denotes the fraction of wort nitrogen present as free amino acids and small peptides readily assimilated by yeast. It is conceptually distinct from total protein: total protein describes potential nitrogen, whereas FAN represents the bioavailable pool that supports yeast growth and fermentation performance. FAN also influences yeast metabolic routing, with downstream effects on ester formation, higher alcohol production, and the overall kinetics of attenuation and maturation.

Adjunct-heavy grists can dilute FAN if the base-malt contribution is reduced, particularly when adjuncts are low in soluble nitrogen or when process conditions limit proteolysis. Conversely, very high levels of assimilable nitrogen are not universally beneficial; the desired FAN range depends on gravity, yeast strain, oxygenation strategy, and flavour targets. In formulation terms, FAN should be treated as a controllable fermentation input rather than as a passive malt statistic.

Practical considerations

When increasing adjunct proportion, consider FAN as a first-order constraint alongside enzyme reserve. If fermentation becomes variable (lag, rate, finishing), FAN is a frequent hidden driver—measure it where possible. Optimise FAN in concert with yeast management (pitch rate, oxygenation, temperature) rather than using nutrients as a blanket fix.

2.5 Lipids

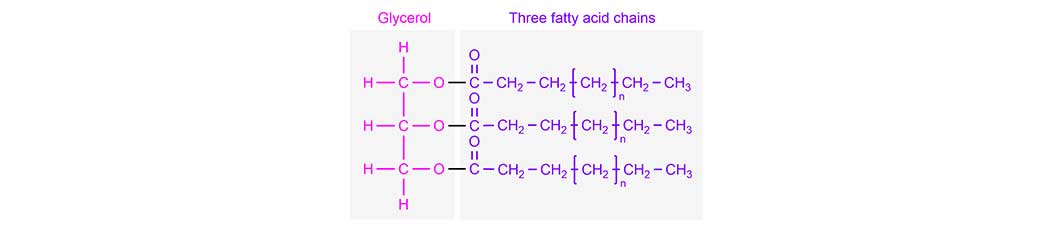

Lipids in cereals include triacylglycerols, free fatty acids, and minor membrane lipids (phospholipids and sterols). Their brewing relevance arises from two principal mechanisms: interfacial activity that can destabilise foam, and chemical reactivity that can contribute to oxidative flavour instability. Lipids may also influence yeast physiology, but in practical brewing their management is typically achieved through yeast handling and oxygenation practices rather than by increasing lipid supply through grist design.

Adjuncts differ in lipid content and in how readily lipids are extracted, which is affected by milling intensity, flaked versus intact structure, and the extent of trub carryover. As a result, lipid-rich adjunct use can be a sensory win (certain texture attributes) yet a stability risk, particularly if oxygen control is weak.

Practical considerations

If foam and shelf-life are priorities, treat lipid-rich additions as “high leverage, high risk”: keep inclusion sensible and tighten oxygen and trub management. Avoid excessive fine milling or process choices that maximise lipid extraction unless you have a clear compensating rationale. Judge lipid decisions by package stability goals, not only by fresh-beer sensory.

Figure 4: molecular structure of a triacylglycerol, a lipid molecule formed by the esterification of one glycerol molecule with three fatty acids

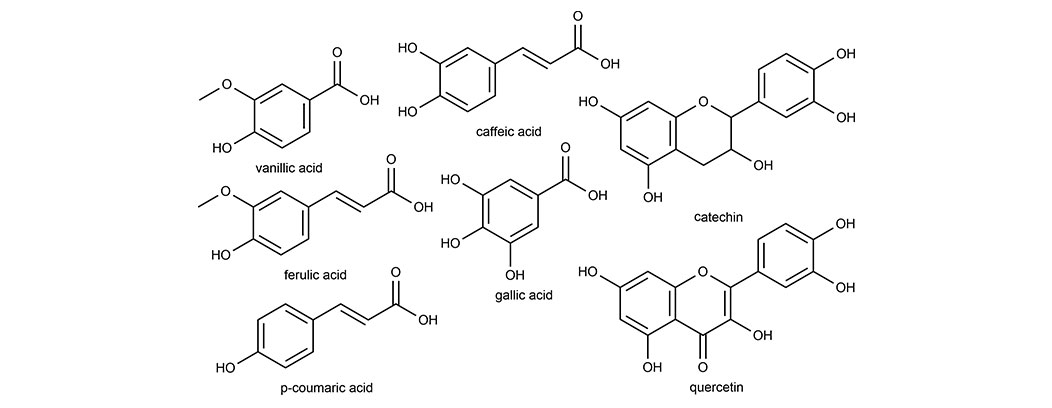

2.6 Polyphenols

Polyphenols are plant-derived phenolic compounds contributed primarily by malt husk material and hops. They include simple phenolic acids and larger tannin-like species capable of strong protein binding. In beer, their sensory signature is often expressed as astringency (via precipitation or interaction with salivary proteins) and their technical signature as haze formation (via polyphenol–protein complexes). Polyphenols are also redox-active; depending on context they can act as antioxidants while simultaneously participating in reactions that contribute to staling when oxygen and metal catalysts are present.

Extraction is process-sensitive: elevated pH, extended contact time, and harsher sparging conditions can increase husk-derived polyphenol pickup, shifting the balance from desirable structure to harshness and instability. Because polyphenols sit at the intersection of flavour, haze, and stability, they are best managed as part of an integrated macromolecular strategy rather than in isolation.

Practical considerations

Manage polyphenols primarily through process discipline (especially pH and sparging practice) rather than assuming ingredient choice alone will solve harshness or haze. If you want “crisp” without astringency, prioritise controlled extraction and appropriate clarification. If you want structure and grip, accept polyphenol contribution deliberately and stabilise the beer accordingly.

Figure 5: molecular structures of several (poly)phenols found in beer wort

2.7 Why flaked adjuncts behave differently from raw cereals and malt

Flaked adjuncts differ from intact or merely milled grains because flaking is typically preceded by steaming or cooking that pre-gelatinises starch and disrupts cellular architecture. This shifts the mash from a diffusion-limited system (enzymes accessing starch through intact cell walls) to one in which starch is rapidly hydrated and accessible, often increasing the rate and apparent completeness of conversion when sufficient base-malt enzymes are present. The same structural disruption can, however, increase the release of soluble non-starch polysaccharides (β-glucans and arabinoxylans) and fine particulate material, elevating wort viscosity and reducing bed permeability, hence the common pairing of flaked oats/rye with lauter aids (i.e. rice husks) and targeted mash control (i.e. β-glucan rest at 40-45°C). Flaking can also modify the extractability of proteins (shifting the soluble nitrogen pool and potentially haze-active fractions) and, for lipid-rich cereals, can enhance lipid extraction, with implications for foam stability and flavour shelf-life. In aggregate, flakes should be treated as a high-accessibility adjunct: efficient at delivering substrate and texture-related macromolecules, but more likely than intact forms to load the mash with viscosity- and stability-relevant species, making process design (enzyme reserve, mash schedule, separation strategy, and oxygen control) the decisive factor in whether their contribution is beneficial or problematic.

- Flakes shift the main constraint from gelatinisation to enzyme reserve + rheology + bed permeability.

- Expect more fine particulate load and faster release of soluble macromolecules: plan separation aids and gentle lautering.

- When scaling flake-heavy recipes, watch your system limits: lauter hardware and recirculation behaviour often set the limit.

- Treat repeatability as a process objective: standardise crush, mixing, recirculation, and runoff rate for consistent outcomes.

3 Practical approach

3.1 Flakes and their impact

Table 1 summarises the principal flaked cereals as functional brewing ingredients, organised by the dominant mechanistic levers described above. For each material, the entry reports (i) the expected tendency of the converted wort to favour fermentables versus dextrin persistence, (ii) the relative non-starch polysaccharide (NSP) load that most strongly governs viscosity and separation behaviour, and (iii) the resulting texture and flavour contributions most often reported in practice. Because these attributes are not intrinsic constants but emergent properties of conversion regime, enzyme reserve, and separation control, the table should be read as a comparative, literature-grounded guide for formulation decisions under conventional mash conditions rather than as a prescriptive specification.

| Type | Wort tendency | NSP load | Texture contribution | Flavour contribution | Example use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barley | Moderate fermentables | Medium | Fuller body; foam support | Grainy; biscuity | Stout, amber, red ales |

| Maize | High fermentables | Low | Light body | Clean; light cereal note | Cream ale, some lagers |

| Oat | Balanced fermentables | High | Silky/creamy fullness | Mild cereal; lightly nutty | NEIPA, oatmeal stout |

| Rice | High fermentables | Low | Light body; crisp finish | Neutral | Light lager, dry pale ale |

| Rye | Moderate to high fermentables | High | Chewy/viscous body | Spicy/peppery note | Rye IPA, Roggenbier, season |

| Wheat | Moderate to high fermentables | Low to medium | Creamy body; strong foam | Soft bready/doughy | Witbier, weizen, hazy IPA |

Table 2 provides typical range as a percentage of the grist for the different flakes, their key constraints, the solutions to use them successfully and a reference style.

| Type | [%] grist | Key constraints | Primary mitigations | Best for (goals / styles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barley | 5–20 | β-glucans/fines can slow runoff; heavier palate if pushed | Rice husks; viscosity-focused mash strategy where needed | Body and foam reinforcement (stout, amber/red ales) |

| Maize | 5–25 | Enzyme and FAN dilution; bed compaction | Ensure ample high-diastatic base malt; consider yeast nutrient | Lightening body while retaining roundedness (cream ale, some lagers) |

| Oat | 5–20 | High viscosity (β-glucans); lipid extraction can affect foam | Rice husks; viscosity-focused mash strategy where needed | Silky/creamy texture, stable haze (NEIPA, oatmeal stout, hazy pale) |

| Rice | 5–30 | Enzyme and FAN dilution; can thin body excessively | Ensure ample high-diastatic base malt; consider yeast nutrient | Crisp, dry, very light-bodied beers (light lager, “dry” pale ales) |

| Rye | 5-30 | High viscosity and enzyme dilution | Rice husks; viscosity-focused mash strategy where needed | Spice and texture without sweetness |

| Wheat | 5–25 | Bed compaction; protein/NSP load increases haze/viscosity | Rice husks; align clarification with style intent | Foam and creaminess; haze support (witbier, weizen, hazy IPA) |

4 Conclusion

Collectively, the literature supports treating flaked cereal adjuncts as functional formulation tools rather than as generic “starch sources”. While their pre-gelatinised state generally removes starch accessibility as the primary constraint, the realised fermentability and sensory outcome are instead governed by malt enzyme reserve and by the accompanying macromolecular load delivered with the flakes. In particular, non-starch polysaccharides (β-glucans and arabinoxylans) can increase wort viscosity and perceived fullness, yet concurrently raise separation risk through reduced bed permeability and slower run-off; nitrogenous constituents (protein fractions and FAN) modulate foam, haze propensity, and fermentation robustness; and minor fractions such as lipids and polyphenols influence foam stability, oxidative shelf-life, and astringency via polyphenol–protein interactions. The practical takeaway is that flake selection and dosing should be made against a clearly prioritised target vector—attenuation versus fullness, brightness versus haze tolerance, and brewhouse robustness versus maximum texture impact—and then realised through a mash and separation strategy designed to manage enzyme capacity, rheology, and oxygen exposure.

5. References and further reading

- Cadenas et al. (2021), Brewing with starchy adjuncts: Its influence on the sensory and nutritional properties of beer. [DOI: 10.3390/foods10081726]

- Faltermaier et al. (2014), Common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and its use as a brewing cereal – a review. [DOI: 10.1002/jib.107]

- Gastl et al. (2020), Cytolytic malt modification – Part II: influence of β-glucan and arabinoxylan on lautering performance. [DOI: 10.1080/03610470.2020.1796155]

- Goode & Arendt (2006), Developments in the supply of adjunct materials for brewing. [DOI: 10.1533/9781845691738.30]

- Habschied et al. (2021), Beer polyphenols—Bitterness, astringency, and off-flavors. [DOI: 10.3390/beverages7020038]

- Hill & Stewart (2019), Free amino nitrogen in brewing. [DOI: 10.3390/fermentation5010022]

- Izydorczyk & Dexter (2008), Barley β-glucans and arabinoxylans: Molecular structure, physicochemical properties, and uses in food products—A review. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2008.04.001]

- Jin et al. (2004), Effects of β-glucans and environmental factors on the viscosities of wort and beer. [DOI: 10.1002/j.2050-0416.2004.tb00189.x]

- Klose et al. (2011), Brewing with 100% oat malt. [DOI: 10.1002/j.2050-0416.2011.tb00487.x]

- Kordialik-Bogacka et al. (2014), Malted and unmalted oats in brewing. [DOI: 10.1002/jib.178]

- Langenaeken et al. (2020), Arabinoxylan from non-malted cereals can act as mouthfeel contributor in beer. [DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116257]

- Lekkas et al. (2007), Elucidation of the role of nitrogenous wort components in brewing fermentations. [DOI: 10.1002/j.2050-0416.2007.tb00249.x]

- Li et al. (2005), Studies on water-extractable arabinoxylans during malting and brewing. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.08.040]

- Mikyška et al. (2002), The role of malt and hop polyphenols in beer quality, flavour stability and haze formation. [DOI: 10.1002/j.2050-0416.2002.tb00128.x]

- O’Connor-Cox et al. (1989), Inhibition of yeast growth by fatty acids derived from starch hydrolysates. [DOI: 10.1094/ASBCJ-47-0102]

- Rübsam et al. (2013), Influence of the range of molecular weight distribution of beer components on the intensity of palate fullness. [DOI: 10.1007/s00217-012-1861-1]

- Schnitzenbaumer et al. (2014), Implementation of commercial oat and sorghum flours in brewing. [DOI: 10.1002/jib.152]

- Siebert (1999), Effects of protein–polyphenol interactions on beverage haze, stabilisation, and analysis. [DOI: 10.1021/jf980703o]

- Steiner et al. (2023), Hydrocolloids in brewing: structure–function links relevant to viscosity, foam, and stability (review). [DOI: 10.3390/polym15193959]

- Stewart (2013), Research advances in brewing: relevance of amino nitrogen and yeast nutrition to fermentation performance. [DOI: 10.1094/ASBCJ-2013-0921-01]

- Vanderhaegen et al. (2006), The chemistry of beer aging – a critical review. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.01.006]

- Vis & Lorenz (1998), Malting and brewing with a high β-glucan barley. [DOI: 10.1006/fstl.1997.0285]

Recent Comments